Print Version

Long-term Effects

Long-term Effects

Rising and Receding Land

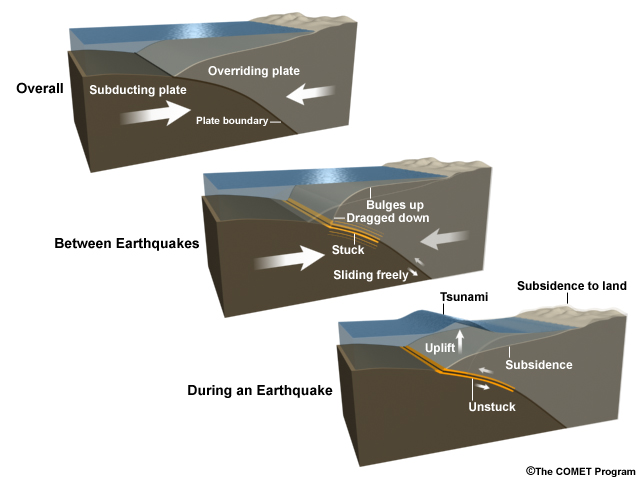

Large, mega-thrust earthquakes at subduction zones can produce long-term changes in the land. The overriding plate was bent like a bow before the quake, and now the land near the fault springs up while the land behind it drops down. This effect can be large, and can make coasts even more vulnerable to tsunamis when land subsides.

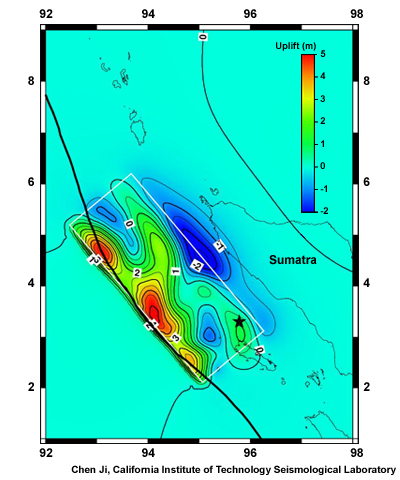

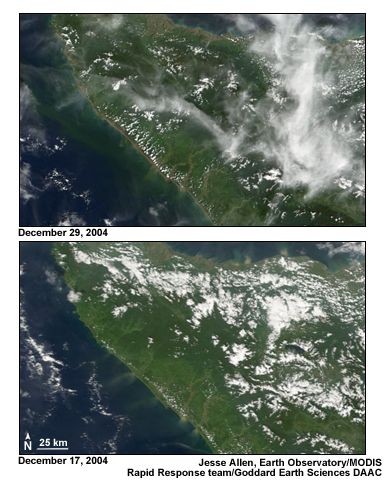

In this image from the Indian Ocean Tsunami, you can see how the plate rose near the boundary and sank further behind it, close to shore.

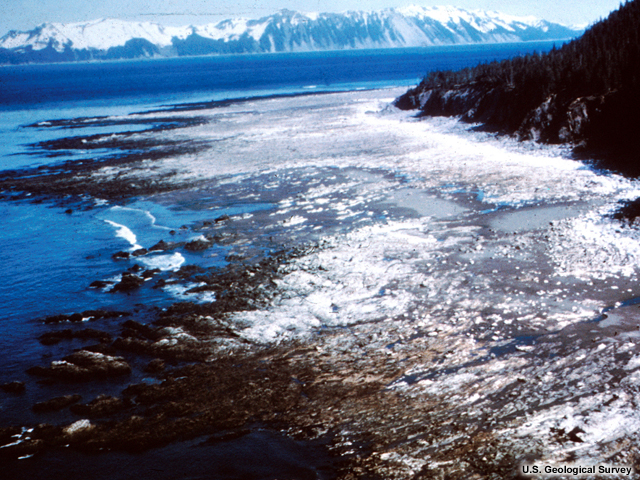

The 1964 Alaska earthquake produced similar effects. This earthquake struck the coast of Alaska near Valdez and forced the entire city to relocate.

In some places land permanently rose up to 15 m (49 ft), and in other places it sank up to two (seven ft). Shipping lanes were altered. Nautical charts of Prince William Sound became inaccurate as depth soundings no longer matched the maps.

In addition to the effects of uplift and subsidence, sandbars in harbors can also shift—blocking the entrance—or disappear entirely.

Coastal environments

People aren’t the only ones affected by uplift or subsidence. Where this happens, coastlines can advance or retreat by several hundred meters, greatly altering coastal environments. In the great Alaska quake, a wetland near Cordova was lifted up, draining it. The clam bed went dry. Migratory birds could no longer stop there, and the plant communities changed.

In other places, the land dropped and plunged conifers into saltwater, killing them and converting the land into wetland and ghost forest.

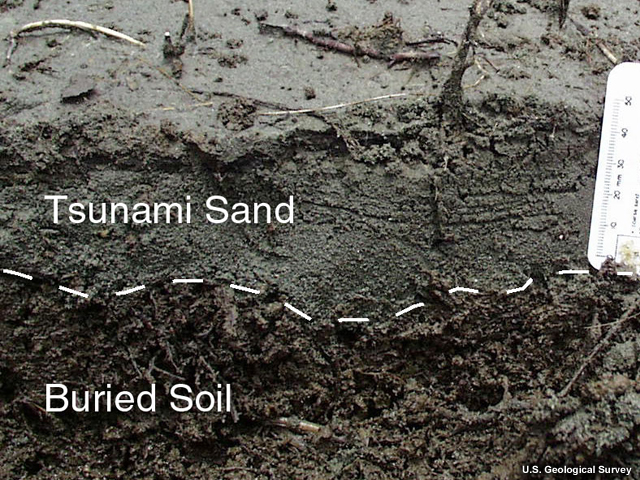

Soil in these places often reveals a centuries-long alternating pattern of sand and dirt—and sometimes ancient buried tree stumps—that tells a story of repeated earthquake-induced elevation change.

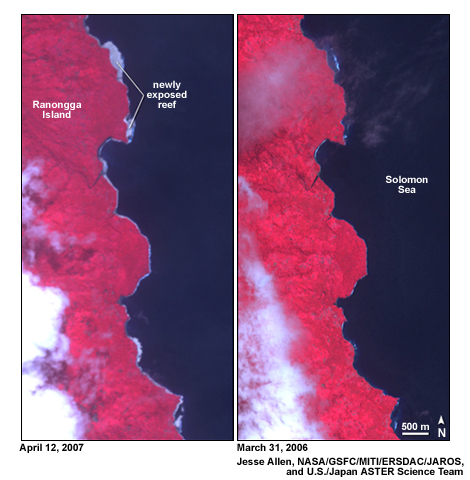

In other parts of the world, different ecosystems suffer similar effects.

In the tropics, salt water-dwelling coastal mangrove forests and coral are often the organisms that suffer from subsidence and uplift. You can see that here on the coast of Ranongga Island in the Solomon Islands after a magnitude 8.1 earthquake raised the coast in 2007. In these cases new land forms on the old reef. At one place in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, tangible evidence of coastal subsidence was experienced by villagers when the holes of mangrove mud lobsters suddenly appeared in their vegetable gardens.

Massive waves may also shear off trees, creating a distinctive “trimline” that takes years to reforest, like this one in Lituya Bay, or this one in Sumatra after the Indian Ocean tsunami.

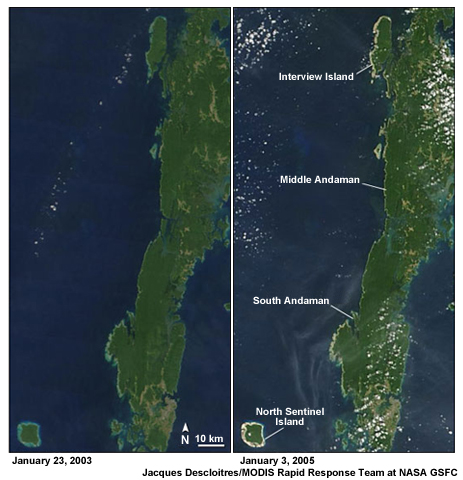

On low-lying islands or flat coasts, vast swaths of forest may be wiped out. In the North Andaman Islands, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami destroyed 3,292.5 hectares (8,100 acres) of coastal forest.

Agriculture

In cases where seawater sweeps over farm fields, the soil grows saltier.

The damage to soil is twofold: direct salt water infiltration of the topsoil, and deposits of salty sand or clay from the sea. The longer stranded tsunami waters sit on the land, the worse the damage will be.

After the Indian Ocean tsunami, 47,000 hectares (116,000 acres) of agricultural land was damaged. Plants were killed by sand or salt and soil fertility plunged. In most cases, abundant rain and irrigation quickly flushed away the salt. Of the 47,000 hectares of farmland damaged, 38,000 hectares were deemed recoverable by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. The other 9,000 hectares were lost for agriculture.

Farmland may also be permanently lost by land recession.

Groundwater Intrusion

Tsunamis can also harm local aquifers by flushing them with saltwater. This happened widely in Asia after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Tsunami waves penetrated the aquifer at dug domestic wells or by infiltrating the permeable sands that usually make up coastal aquifers. In Sri Lanka, over 40,000 drinking water wells were either destroyed or contaminated in these ways.

Earthquakes that generate tsunamis may also crack the bedrock of the aquifer, making it even easier for seawater propelled by tsunamis to infiltrate them, as happened at Neill Island in the Indian Ocean after the 2004 tsunami. Groundwater recharge from monsoons or other rains may help dilute these problems with time, but freshening of wells can take months or years.

Summary Questions

Question 1

What are the chief long-term effects of tsunamigenic earthquakes? (Choose all that apply.)

The answers are A, B, C, and D. All of these changes can be experienced after major tsunamigenic earthquakes.

Question 2

Which of the following are long-term environmental effects of tsunamis? (Choose all that apply.)

The answers are A, B, and D. Subsidence does not alter the ocean temperatures of nearby currents.

Question 3

What are the ways tsunamis can be destructive to agriculture? (Choose all that apply.)

The answers are A, C, and D. Tsunamis do not strip soils of nutrients. Erosion can, however, carry soil away. Deposition of sediments and infiltration of saltwater by tsunamis are much more common.

Question 4

What are the ways tsunamis can damage aquifers? (Choose all that apply.)

The answers are B and C. Tsunamis cannot drain or pressurize aquifers.

You have completed the module. Please consider completing the quiz and survey linked at the bottom of the left-hand menu.